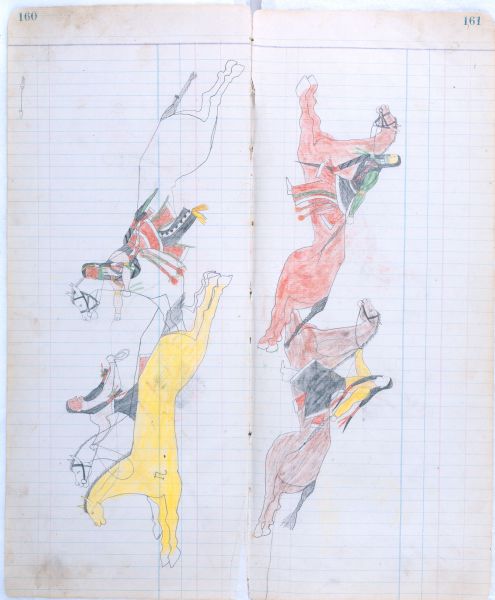

PLATE 160-161

Ethnographic Notes

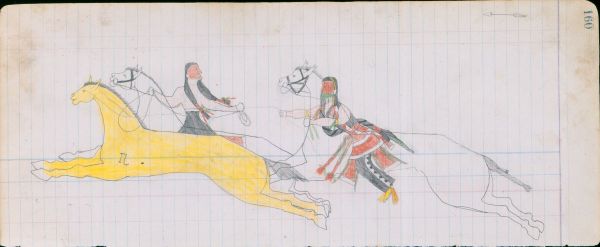

Arrow identifies himself by his name glyph at the upper right of Plate 160, and by the small feather tied to the tail of his white stallion. The other rider is his Nisson comrade, whom we recognize from the red face paint in Plates 134 & 136, and the white horse he rode in Plates 112 & 146. Even though the buckskin mare has been branded, this is not a depiction of a horse raid on some ranch herd, for the Cheyennes would in that case be driving the animals a long distance away, to safely outdistance any pursuers. Instead, the fact that a team-roping endeavor is in progress tells us that the mare is running wild.

"...as certain horse catchers became more skillful with the rope, they began to carry extra ropes coiled and tucked under their belts. Another man on a good horse followed the one who used the rope, and when the wild horse was noosed, the second man took the rope and choked down the wild animal, leaving the roper free to follow another wild horse" (Grinnell, 1923, I: 293).

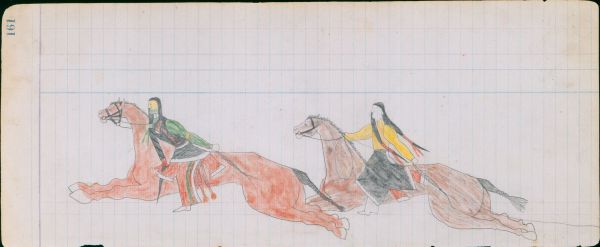

Grinnell also notes that Cheyennes often did not throw a lasso, in cowboy fashion, but tried to overtake the horse and drop a noose over its head. That is clearly what the Cheyenne is attempting here, and Arrow already holds the end of the rope, in preparation for stopping the buckskin. Plate 161 either shows another team; or perhaps a relay of other relatives who will follow the "roper" after the next animal, as Arrow struggles to subdue the buckskin.

The manufacture of lariats of the type used here was a principal Cheyenne male occupation.

"A good riata ('lasso') requires a great deal of labor and patient care...It is generally made of the raw hide of buffalo or domestic cattle, freed from hair, cut into narrow strips, and plaited with infinite patience and care, so as to be perfectly round and smooth. Such a riata...runs easily and quickly to the noose, and is as strong as a cable. To make these articles is all that the male Indian does in [the] winter" (Dodge, 1882: 252).

Among the equipment which the Army captured when they plundered the Dog Soldier village at Summit Springs in July 1869, were two hundred rawhide lariats (Afton, et. al., 1997: 320-21), indicating (in a village of eighty-four lodges) that two or three such lariats per family was the norm.