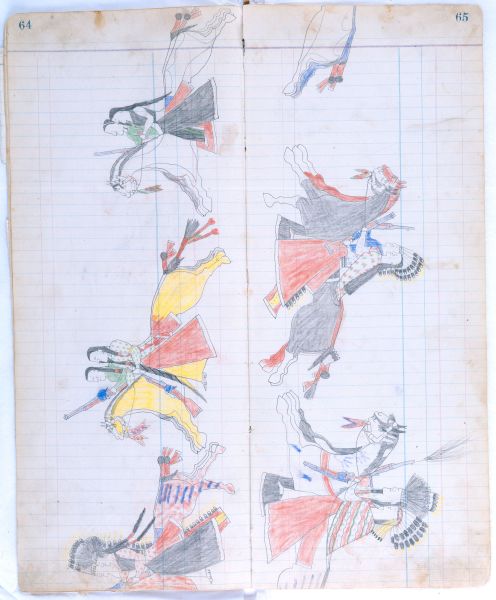

PLATE 64-65

Ethnographic Notes

A Dog Soldier war party parades around the circle of a Cheyenne village, some firing guns in excitement, before leaving to attack the enemy. The fact that the tails of all their horses are wrapped indicates this is not merely a display leading to a convivial feast, but that their purpose is belligerent.

The group may be recognized as Dog Soldiers from two very distinctive, globular headdresses. One of these is worn by the near rider, far left, in Plate 64; the other by the back rider, far right, in Plate 65. The cap of this type of headdress is completely covered with black raven or crow feathers, each tipped with a spot of white-gypsum glue. These feathers stand out in hemispherical profile, with a crest of six golden eagle tail feathers rising in the center, gypsum spots and yellow horsehair at the tip of each. There were six such headdresses worn by officers of the Dog Soldiers: two colored black, two yellow, and two red, with corresponding full-body paint---see Berlo, 1996: Plate 52.

It is important to note that not all members of the Dog Soldiers wore such headdresses, but only certain of the officers. Dorsey (1905, No. 1: Fig. 2) shows a Dog Soldier with his hair worn loose, and Arrow here depicts two others. Other members wore other types of headdresses, if they chose, or none at all. The man at far right, Plate 65, wears a simple crown-style war bonnet of golden eagle feathers.

Two very similar and distinctive eagle feather headdresses, each with a long trailer visible under the belly of the rider's horse, are shown. The repetitive nature of these suggests that they may be characteristic of Dog Society usage. We should be alert for other examples that may exist in collections of Cheyenne drawings not yet published. The two headdresses in question are worn by riders on the far side in Plate 64, left, and Plate 65, center. These are only partly visible. The cap consists of a standard, golden eagle crown headdress, with beaded browband and yellow-colored ermine pendants. A single row of eagle feathers extends down a long trailer sewn to the back edge of the cap. A distinctive characteristic of each trailer is that it is composed of three, longitudinal strips sewn together. The center strip is yellow, while the two, outer strips are red, with the white selvedge which indicates they are wool trade cloth. The trailer in Plate 65 shows white selvedge against the center strip too, meaning that it is yellow trade cloth. In Plate 64 the yellow central strip has no selvedge, so it could be made of painted leather. In these views Arrow shows the bottom of the trailers, as if they are blown sideways, with only the dark tips of the eagle feathers visible beyond the upper edge. The feather tips have standard white spots of ermine fur, or gypsum glue, and yellow-dyed horsehair.

Although originally they were one of the four warrior societies founded by the Tsistsistas culture hero Sweet Medicine, by the 1840's the Dog Soldiers had formed an entirely separate village, centering their territory on the upper Republican and Smoky Hill rivers, in western Kansas and eastern Colorado. Almost immediately thereafter, the ever-increasing flow of emigrants along the Platte valley just to the north caused continuing problems for the Dog Soldiers.

When gold was discovered near Denver in 1858, tens of thousands of miners forced a new road up the Smoky Hill, directly through the Dog Soldiers' best buffalo country, seriously threatening the livlihood of the group, and the Cheyennes as a People. The Dog Soldiers were strong to defend their rights, which often brought them into direct conflict with White civilians and the U.S Army.

Their courage and success attracted many others to join them. In the mid-1860's it was reckoned that half the Southern Cheyennes were in the Dog Soldier camp. As early as the 1840's, groups of Brule and Oglala Sioux were also affiliated with the Dog Soldiers. Sometimes they were referred to as the "Cheyenne-Sioux" (Grinnell, 1923, II: 68).

After Col. Chivington's Colorado militia massacred Black Kettle's village at Sand Creek in 1864, the survivors fled 50 miles on foot through the snow to reach the Dog Soldier village on the Smoky Hill, and seek assistance. For five years thereafter, the Dog Soldiers were at the forefront of Cheyenne resistance, until their village was attacked and destroyed at Summit Springs, Colorado, in July 1869. This loss dispersed the survivors among both the Northern and Southern Cheyennes, but chiefly they remained in the south, reverting to their original status as one of several military societies. That was their situation during the fighting of 1874-75.

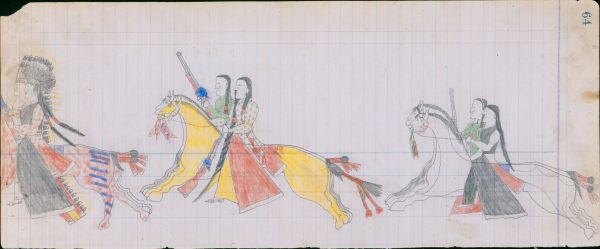

Grinnell learned that when the Dog Soldiers paraded, as shown here, "two of the bravest take the lead, and two other brave ones come behind...In certain ceremonial parades the column of Dog Soldiers were usually followed by a horseman not a member of the society..." (1923, II: 67). On this particular occasion, Arrow depicts himself being so honored by the Dog Soldiers, for he is the man riding the buckskin horse in Plate 64. We may recognize the white and red plaited wrapping of his hair on the left side, together with the otter wrapping on the right side, already seen in Plate 32. The flesh side of his otter hair wrap is painted yellow. Arrow carries the Ballard carbine which he captured in Plate 13, grasping it by the barrel. He wears a new pair of brain-tanned leather leggings painted yellow, beaded moccasins, a red wool breechcloth, calico shirt in blue polka dot pattern, and has a red trade cloth blanket laid across his thighs.

The man beside him, wearing a green shirt and carrying an 1873 Winchester carbine, appears to be riding Arrow's white stallion with the iron-grey legs. This man may be the Elk Society shirt wearer shown in Plate 163, who appears often as Arrow's special comrade in later drawings of the ledger. It is likely this man was Young Bull Bear, as explained in the opening essay. As both men were proven fighters and close friends, the Dog Society would likely have been happy to have their company and assistance. The horses of both men sport silver-mounted headstalls, with spotted kerchiefs tied near the bits.

The Dog Society had a curious tradition that if any member ever dropped anything, whether the smallest trifle, or an entire packhorse-load of meat, he was forbidden to pick it up himself. The functional reason for inviting non-society members along on Dog Soldier war parties was to perform this task of recovering dropped articles, if it became necessary. Undoubtedly the guests were lavishly rewarded for their services; and it is likely that prominent Dog Society members often dropped some piece of their regalia purposely, merely so they could recognize and reward leading warriors of other societies. Such exchanges of social courtesy were a means of strengthening tribal solidarity, and of attracting others to the Dog Soldier cause. Arrow's purpose in this two-page composition is to show that he and his Nisson-relative had been so honored.

Note that the Cheyennes are very well armed, three carrying the brand-new, 1873 model of Winchester carbine, recognizable from the blued-steel sideplates, and the loading tube under the barrel (Watrous, 1966: 17). Others carry partly-visible, single-barrel carbines which might be a variety of other makes, including Spencer, Sharps, Joslyn, Ballard or Starr. The man at far right in Plate 64 displays a revolver. It is certain that most of the others had these as well. Indeed, when Roman Nose confronted Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock in 1867, he was described as having a Spencer carbine, and "four heavy revolvers...stuck in his belt," in addition to a bow and arrows (Hoig, 1980: 97).

Col. Richard Dodge, who had often found himself facing Cheyenne firepower, recalled:

"Every male Indian who can buy, beg, borrow or steal them, has now firearms of some kind. They are connoisseurs in these articles, and have the very best that their means or opportunities permit. Every man having to procure his own arms when and how he can, there is no uniformity of make or calibre---a fortunate circumstance for his enemies, but extremely annoying to the Indian...Some guns of a band were almost always out of use on this account; but necessity, that great 'mother of invention', has so stimulated...the Indian, that if he can only produce the moulds for a bullet that will fit his rifle, he manages the rest by an ingenious method of reloading his old shells peculiar to himself. He buys from the trader a box of the smallest percussion caps, and making an orifice in the center of the base of the shell, forces the cap in until it is flush. Powder and lead can always be obtained from the traders; or, in default of these, cartridges of other calibre are broken up, and the materials used in reloading his shells. Indians say that the shells thus reloaded are nearly as good as the original cartridges, and that the shells are frequently reloaded forty or fifty times.

"Many of the Indians possess revolving pistols of the very best kind, and have much less trouble on account of the ammunition, the calibre being more uniform" (Dodge, 1882: 422-23).

An interesting detail, which is repeated in an Elk Society parade shown in Plate 163, is the cloth capes worn by two men in Plate 65. Printed calico is used here; apparently red wool trade cloth in Plate 163.

Two of the horses in this parade are painted with symbols of the riders' coups. In Plate 64 the strawberry roan in the lead has nine blue stripes painted down the left hip and leg. Each of these represents a recognized exploit. In Plate 65 the white stallion at right has similar blue stripes on the hip, and blue "wound symbols" (representing the round bullet wound, with descending lines to symbolize dripping blood) on the left foreleg. Compare actual bullet wounds shown in Plate 9, which inspired these symbols.

"If one man had had his horse shot under him, he painted his steed with a round dot to show where the ball or arrow had entered, generally using red paint" (Grinnell, 1923, II: 61).

On the neck of this same horse are shown two prints made by dipping the hands in blue paint, then pressing them on the animal's coat.

"...it was highly creditable to ride over an enemy on foot, and in the old time dances of the different [societies], horses were frequently painted with the prints of a red hand on either side of the neck and certain paintings on the chest intended to represent the contact of the horse's body with the enemy" (Grinnell, 1910a: 302).

Although Grinnell in this quotation was referring specifically to the Blackfeet, the same symbolism was employed by their Algonkian relatives the Cheyennes; and while the hand prints here are painted in blue, compare Plate 124, where red prints appear.