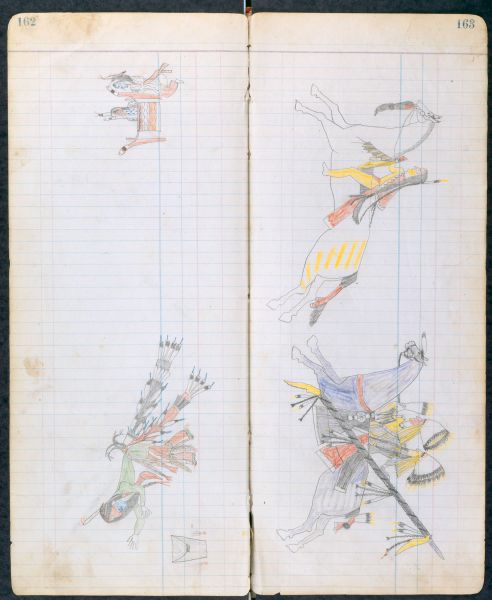

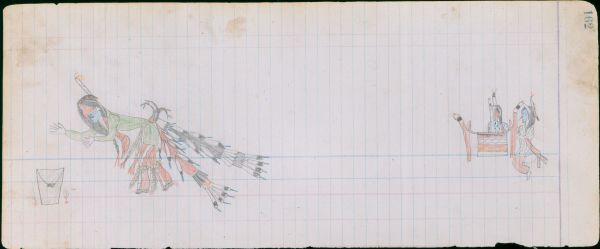

PLATE 162-163

Ethnographic Notes

Plates 162 - 165 represent the preparations for departure of an Elk Society war party. This included a shamanistic forecast, depicted in Plate 162; and a parade of the camp, shown in the other three Plates, understood to represent a continuous line of horsemen. The departing men dressed in their finest war clothing, and carried their shields and weapons, so that if they were killed, their families and friends might have this last, glorious memory of how they appeared, in all their handsome strength. Officers of the society carried the implements indicative of their responsibility---their lances and whips.

The men would all be singing Wolf Songs, melodies of longing for the sweethearts they were leaving behind, with lyrics such as:

"I do not see my love. (To her:) Come out of your lodge, I need to see you."

Or again:

"My love, do not scold me [for going], I love only you" (Grinnell, 1903: 317 & 321).

These would be repeated again and again, like a roundelay. After circuiting the camp, perhaps many times, the leaders would start away, the whole party changing to a verse such as:

"I am going to search for a man. If I find him, there will be fighting. Perhaps he will kill me" (Grinnell, 1923, II: 393).

This would be kept up as long as they were within hearing distance of the camp. Mothers, wives, sisters, daughters and sweethearts would stand in crowds along the edges of the lodges, weeping as their men rode away, the proud song growing fainter, until it was swallowed by distance.

Then began perhaps many weeks of agonized waiting, while each of those who remained behind---including male friends and relatives as well---kept firmly in memory the last glimpse of their loved ones, like the images Arrow shows us here.

Plate 162

When a proven war leader decided that he would head a party against the enemy, he approached a respected seer, and offered him a sacred pipe filled with tobacco. Such a person is called Ovanhetan, literally "miraculous man", often glossed in English as "medicine man" (Petter, 1915: 677).

Grinnell obtained only the barest glimpse of what such a seer actually did:

"...the leader said to the medicine man, 'We wish to go to war,' and offered him the filled pipe. The man took the pipe---thereby agreeing to perform the necessary ceremonies---it was lighted and he smoked, and then sang a medicine war song. Then he was likely to say to them, "It is well, my friends; you are to go to such and such a place, on such and such a stream; there you will find people---your enemies', mentioning the tribe" (Grinnell, 1923, II: 10).

Doubtless this drastically condenses the actual process, and makes it sound as if the seer merely invented a destination, on the spur of the moment. It should be obvious that a great deal more must have been involved. For the first time in nearly a century since Grinnell's inquiry, this earlier drawing by Arrow provides further documentation of what an Ovanhetan actually did.

One of the forms of augury practiced by Cheyennes on their way to war was to capture and kill a badger---a creature of immense physical and spiritual power, which dwelt in the Deep Earth. The badger was eviscerated at dusk, laid on its back on a bed of sage, its head to the east, and its blood allowed to collect overnight in the open, abdominal cavity. Early in the morning, members of the party who wished to learn their fate stripped themselves naked, unbound their hair, then went one by one to stare into the badger's blood, as into a mirror of the future. If they saw themselves reflected in wrinkled old age, they knew they were invulnerable. If their visage appeared hacked and scalped, they immediately abandoned that warpath, and returned home. Apparently the experience was so unnerving to many that "the Cheyennes became afraid to practice this mode of divination, and abandoned it" (Grinnell, 1923, II: 26-27).

Arrow shows us here what must be a modification of that same technique. Rather than blood, the seer has probably chosen water reflected from the darkened depths of a tin pail. This he has sanctified by placing it at the center of four small mounds of earth called Hohaneno (Petter, 1915: 721). In this lateral view, only two of these mounds are shown. This arrangement corresponds to the altar of the Massaum ceremony, where a central circle represents the cavern under the earth in which buffalo (and badgers) are created, surrounded by the four Vosoz or Sacred Mountains which are believed to hold up the Sky, and in which dwell the Maheono, or Spirits of the Four (ordinal) Directions: Southeast, etc. (Grinnell, 1923, II: 292; Schlesier, 1987: 92-93). The altar, then, is an image of the world; and an analog of the war shield design discussed with Plate 17.

On each of the four mounds the seer has placed a burning coal, and on these has sprinkled one of the holy herbs, probably the one called "strong medicine"---Anaphalis margaritacea (Grinnell, 1923, II: 187-88), used primarily for protection in war.

"Fire and burning have a very prominent part in all Cheyenne ceremonials, hence the importance of the pipe. An old priest, Hotoa-namos [Left-hand Bull] told the writer that in the different ceremonial burnings the fire ingredients, the hot coals, the flames, the smoke, have all their ceremonial meanings. By shining for years upon growing trees or plants, the Sun has imparted of its strength and life to the plant substance...Heat and light is needed for life, hence such symbols and ceremonial burnings. This thought underlies the burning of incense to 'loosen' the beneficent fragrance inherent to some plants...The fragrance and therapeutic power of plants is given to them by the Sun, which in its turn received it from Maxemaheo (Supreme Mysterious One)" (Petter, 1915: 200).

The smoking incense or "strong medicine" is shown by Arrow rising around the pail of water as the Ovanhetan approaches. We may presume that he comes dancing, for two singers at the right provide him cadence and accompaniment with a sonorous drum suspended from several support sticks. Commonly, such a drum required four supports; again in this lateral view, only two are shown. The Cheyenne word for such a diviniatory performance is Nadvavosoe, "I dance to prophesy" (Petter, 1915: 676). Arrow's drawing shows the reality behind Grinnell's too glib "the man...sang a medicine war song..."

Through fasting, prayer, many years of contemplation, and the grace of Maxemaheo, the Ovanhetan had established a psychic relationship with one or more supernatural powers:

"Names of some Cheyenne familiar spirits:

Oxtamatovaosz = Smoke (from fire or vapor); Vooxmomeha = Cloud Heading, or Vapor Meeting; Maako-oxtanevoo-sansz = Badger" (Petter, 1915: 368a).

It was such spirit powers, and others beyond counting,which conveyed to the Ovanhetan the information he sought for the departing war party. "Badger" provides the technical clue for the type of gazing engaged in by the seer. "Smoke", or "Vapor Meeting" are appropriate spirit nicknames derived from the exact process shown here: four small columns of incense rise around the pail, their vapors converging above the mirrored surface of the water. This replicates the time before Creation, when all was water, cloaked in fog (Grinnell, 1923, II: 337-38; Petter, 1915: 489, "Fog").

It is also significant that the Cheyenne word Veho (Grinnell's spelling is Wihio), the name of the trickster-hero, can mean both "wisdom", and something "enclosed, [like]...water in a keg' (Grinnell, 1923, II: 89). The Ovanhetan here seeks knowledge from such enclosed water. As tendrils of incense smoke weave shifting patterns above the reflective surface, the man of knowledge gazes deep, seeking the right direction, the proper distance, specific location and a vulnerable enemy. When these portents have been sifted from the vapor, he will be ready to tell the war party where they should go.

In the history of the human family, this predictive, shamanistic strategy has a time-depth that must be on the order of tens of millenia---at least 20,000 years, and probably twice that, considering that it is found alike across Eurasia, as well as in North and South America. Before the young Alexander of Macedon left mainland Greece, he journeyed to the oracle at Delphi, where the Pythia (the seeress) gazed into the vapors above a caldron of water, told him he would conquer all the world, and sent him east.

The feathered construction tied with a yarn sash around the waist of the Ovanhetan is referred to in the ethnographic literature by the absurd term "dance bustle", because it hangs above the rump, and reminded Victorian observers of their own ball gowns. Among Plains Algonkians, such a construction symbolized the Thunderbird, as a metaphor for overwhelming power in war. For a related, Arapaho example see Kroeber, 1902: Plate LXXIV; or Feder, 1971: Plate 47.

The base of the bustle was a piece of buffalo parfleche, perhaps a foot square, folded over the belt sash and the halves tied together. On this has been mounted the stuffed head and neck of a golden eagle, its scimiter beak curving down as it faces backward from the dancer's waist. The eagle's tail with spread feathers is tied below the head; and two trailers representing the bird's wings flare out from the lower corners of the base. Tied to the trailers are feathers from birds of prey, and of carrion: the black-tipped, white feathers are those of golden eagles; the solid-white ones are from bald eagles; and the smaller, solid-black feathers are those of ravens. All such birds might be found scavenging the dead bodies on a battlefield. The Ovanhetan here is harnessing the birds' preternatural powers of sight: as they are able to find dead bodies, he too is searching. Much has been written about the shamanic practice of "magical flight". Arrow has here preserved his eye-witness description of the actual event.

On either side of the eagle's head is fixed a "spike" feather from the forewing of the bird, the shafts manipulated to curve upward, and narrow strips of rawhide wrapped with porcupine quills tied along the length. These are similar to the spike feathers tied to the circumference of Arrow's war shield in Plate 27. Here, they probably also represent lightning: note that they curve past the eyes of the eagle---the Thunderbird is said to shoot lightning from its eyes.

Blue-dyed horsehair at the tips of the feathers symbolize tendrils of static electricity, which may be seen arising from the horns and ears of ruminants, just ahead of an approaching thunderstorm (Dobie, 1941: 90-91; Abbott & Smith, 1939: 66-67; Collins, 1928: 155-58). Such electricity was perceived by Cheyennes as part of the weaponry of the Underworld Powers, particularly the Ax'xe, a monstrous, bull-like creature thought to live in springs. The Thunderbird and the Ax'xe are eternal enemies, and form the archetypes of Cheyenne war imagery. The presence of the blue "electricity" here indicates that the Tunderbird has conquered its enemy, and consumed his power.

In the sweatlodge ceremony, a buffalo-skull altar is employed which represents the Ax'xe. Before the departure of a war party, members would partake in such a ceremony, conducted by the Ovanhetan. During this sweat, each man would offer small pieces of his own flesh, cut from his arms and legs, as a kind of innoculation: small injuries, to prevent larger ones. This flesh was "fed" to the Ax'xe, by being placed under the buffalo-skull altar (Grinnell, 1923, II: 10).

Note that the left trailer of this bustle is red---either painted leather, or wool cloth---and the right trailer is black. This dyad charts the male/female opposition of the Cheyenne world: the male south is red, while the female north is black (Schlesier, 1987: 93; Grinnell, 1914: 369). The Ovanhetan, therefore, is conceptually facing west, or southwest---the dwelling place of the Thunderbird---as he approaches his mystical mirror.

Cheyennes associate the skunk and the badger as related animals, and both are thought to have great powers for healing (Grinnell, 1923, II: 104, 146). Partly, this is because both may live in burrows---that is, they are Underground creatures. Also, both wear "war paint" that is black and white. Generically, of course, both are mustelids, and Cheyennes realize this too. It may be significant, therefore, that the Ovanhetan wears black and white skunkskin garters, over his red trade cloth leggings. Small, brass hawkbells are laced along these garters, adding their plangent tinkling sound to his movements.

His moccasins are partly beaded in a pattern of diagonal stripes along the edge. The unbeaded leather is painted green, with red-painted fringes down the toe, and at each heel. The shirt worn by the Ovanhetan is of green cloth, perhaps intentionally connoting the thunderstorms of springtime, when black clouds above the Southern Plains really can appear green.

The prophet's face is painted in halves, red over blue. The parting of his hair, and the perimeter of his scalplock are also painted red. A bald eagle tail feather is stuck upright into his scalplock. This is painted with two, transverse red stripes, probably representing first coups, and indicating that the seer has personal experience in the business of war.

Feathered bustles were widely used among the Cheyennes' Lakota allies, where prior to ca. 1875 they were part of the regalia of the Omaha warrior society (see Bad Heart Bull, 1967: Plate No. 31). Later, such bustles were used as regalia of the Grass Dance Society, a fraternal organization that became popular among many Plains tribes, and has survived as the modern powwow. Photographs showing Lakota feathered bustles similar to the one worn by the Ovanhetan appear in Cowdrey, 1999: Figs. 52 & 53.

A feature of Grass Dance Society ceremonies during the 1880's and later was called the "Kettle Dance", wherein four men wearing feathered bustles would charge a tin pail or brass kettle filled with portions of cooked dog meat, representing dead enemy warriors. Small pieces of this meat would be speared from the kettle, and "fed" to the dance bustles, indicating they also symbolized raptors. The dog meat would then be distributed as a sacramental feast among the dancers and spectators (Bad Heart Bull, 1967: Plate No. 408; Wissler, 1912: 50-51). Perhaps among Lakota people of an earlier day, the Kettle Dance also had a divinatory, shamanistic purpose.

The Ovanhetan's "dancing to prophesy", the flesh sacrifices and sweat lodge ceremony to pray for the departing warriors, and other preparations might occupy several days, as recounted by George Bent, himself an Elk warrior:

"All the 'charms' that are worn in battle must be fixed up, putting new feathers on war bonnets, shields, lances; or [if] lock on Scalp Shirt is missed, another one is put on. If person goes into battle without these being replaced, person would get killed or wounded...Of course, these were put on again by Medicine Men. These Medicine Men asked blessings in their way, to Great Spirit, while putting these things on. These Medicine Men had to be feasted while doing all this" (Bent, 1904-1918, May 15, 1906).

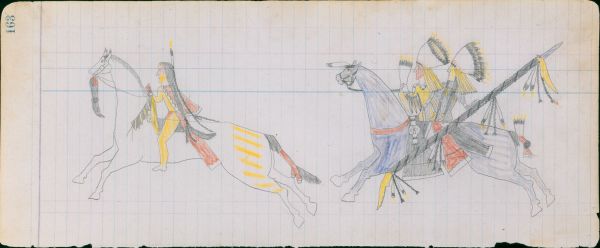

Plate 163

Here begins the Elk Society parade. George Bent described such an occasion in 1865 when the entire tribe, together with the Oglala Sioux and Northern Arapahoes, went off to attack the fort at Platte Bridge:

"Those that got ready first rode out to the opening of the circle of the village 1/2 mile, and waited until everybody got there. Each band formed in line. Bravest ones in battle were told to take the lead and [rear positions]...These bands rode around the inside of the circle of the village. The line [all the warrior societies of three tribes] must have been 2 miles long. Everybody was singing war songs. Women and old men standing in front of the lodges singing as the bands rode by" (Bent, 1904-1918: May 15, 1906).

Leading this parade of the Elk Society war party, as Bent specified, is one of the bravest of the tribe, a man like the Elk warrior Roman Nose---so imbued with spiritual power that he could ride into battle virtually naked, protected only with a mystical covering of paint.

"The naked fighters among the Cheyennes...were such warriors as specially fortified themselves by prayer and other devotional exercises...Their naked bodies were painted...each according to the direction of his favorite spiritual guide, and each had his own medicine charms...A warrior thus made ready for battle...placed himself in the forefront of the attack, or of the defense"(Marquis, 1931: 84).

"The only naked Cheyenne [in the Battle of the Rosebud] was Black Sun...who...spent a long time at getting ready. All of his body was colored yellow. On his head he wore the stuffed skin of a weasel..." (Marquis, 1931: 202).

While not entirely naked, another of the bravest Northern Cheyennes in the Rosebud battle was Young Black Bird (later called White Shield), son of Spotted Wolf. The father had received visionary instruction from a kingfisher, and could understand its language. With blue clay from a spring he painted four kingfishers on the son's horse, on each shoulder and hip.

"...as they were getting near to the enemy...his father dressed him, painting his whole body with yellow earthpaint...he took a scalp, and placing the horse so that it faced south, he tied the scalp to its lower jaw. He then put his own war shirt on White Shield...[and] tied the [stuffed] kingfisher to his son's scalplock" (Grinnell, 1915: 337-38).

Like these other brave Cheyennes, the Southern Elk warrior shown here is colored entirely in yellow earthpaint, save for the upper half of his face, which is light red, with a brilliant, scarlet rainbow curving above the brow. While yellow was a principal color of the Elk Society in the context of lightning, yellow is also indicative of the Sun, and its life-sustaining power (Powell, 1973: 5). Surely that is the context intended here. Nonono, the rainbow, is the snare which the Thunderbird uses to trap its enemies (Petter, 1915: 170-71). Here, the man himself becomes the trap, and Death incarnate.

The term "naked" warrior always refers to the limbs and upper body, and presupposes that---as here---a breechcloth was worn. This man also has a cape, this and the breechcloth made of red wool trade cloth. The edges of the cape are bound with white cloth cut or folded in a zigzag pattern connoting the Elk Society's lightning motif. A single, golden eagle tail feather adorns this man's scalplock, which is bound at the bottom with narrow, twisted strips of otterskin. The ends of his neatly-parted hair are wrapped with the same material.

The lightning motif is repeated and ramified by the serrated edge of the carved wooden quirt or whip which dangles from his left wrist. James Mooney (1905) noted that some officers of the Elk Society carried a club that had a foxskin guard; but neither he nor anyone else ever described it. In one of his most significant cultural images, Arrow here documents the appearance of the Elk Society quirt. There can be no question of the context, for this quirt and another (in Plate 165) appear in sequence with two Elk Society straight lances.

The quirt handle of Elk warriors was painted in diagonal sections or stripes of black and yellow. There were two rawhide lashes; and often the skin of a kitfox formed the wrist loop, or guard. In this example, the foxskin has been cut square across the neck, and the flesh side of the skin painted red, with two black crosses (stars?) visible above the man's hand. The example in Plate 165 is slightly different. Apparently the black and yellow stripes were the essential, identifying motif. Compare the 1898 photo in Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 57, which shows precisely this type of quirt carried in an Elk Society procession, right beside a crooked lance.

The white horse ridden by this "naked fighter", with its forked ears, may be the same animal Arrow rode in Plate 160. This suggests an especially-close relationship between the men. They may well have been Nisson relatives---brothers or first cousins---who shared possessions, and often went to war together. Here, yellow stripes signifying the rider's coups are painted on the rump, and down the horse's left rear leg. The horse's tail is wrapped; and an enemy's scalp dangles below the jaw. This signifies that the animal had been ridden before, when an enemy's soul had been "eaten". Like the scalps shown in Plates 19 & 21, this one is bisected vertically, with the halves painted red and black. The long hair has been tied in an overhand knot.

Two men ride together on the second horse in the procession. The first of these men is an officer of the society, as indicated by his yellow-painted scalp shirt (Dorsey, 1905: 16; Petter, 1915: 777-78). In fact, he is Arrow's close friend and courting partner, likely also a Nisson relative, who has been depicted so often before. His face is painted with the combined red background, and lightning motif below the eyes, shown in Plates 90, 100, 108 & 112. Recalling that lightning is shot out from the eyes of the Thunderbird, we understand that the merest glance of this man will mean death to his enemies. Without care, it could even be deadly to his friends (Grinnell, 1923, II: 145).

Seated behind the shirt wearer is Arrow, carrying the otter-wrapped straight lance seen earlier in Plates 7 & 27. He is dressed much as he was in Plate 5, and wears the same eagle feather headdress. The fact that Arrow is riding double in this parade context indicates that on some prior occasion---perhaps the one shown in Plate 9, when Arrow's horse was killed---this friend had rescued him while under fire from the enemy, taking Arrow up behind him on his horse. This was one of the bravest of war accomplishments, and the specific obligation of a scalp shirt wearer:

"In battle he was required to be the first man to advance, the last to retreat. If a comrade's horse was shot from under him, or if the comrade was otherwise left afoot, it was the scalp shirt wearer who was obligated to rescue him. If the shirt owner failed to do so, he was required to give up his scalp shirt and to listen to the jeers of the people for the rest of his days" (Powell, 1973: 9).

In addition to a scalplock fringe, this shirt has yellow tubes of ermine fur hung along the sleeves. Strips of white and black beadwork adorn the arms, as well as the neckpiece. Probably similar strips were sewn across the shoulders, as on most Cheyenne scalp shirts; a somewhat crowded composition has dictated that they be omitted here. The shirt wearer has leggings made of dark blue (black) wool trade cloth; and a blanket of the same material adorned with a beaded strip, laid across his thighs. He carries a fan made from the tail of a golden eagle, the handle wrapped with a yellow-spotted, silk kerchief.

Arrow is dressed primarily in black, with his face painted entirely yellow. A blanket of red wool trade cloth is carried across his thighs. His hair is wrapped with strips of otter fur, but these are less elaborate than usual. Note, however, that they are tied at top and bottom with yellow-painted leather, and appear to include rounded packets of some protective material---either herbs, or possibly small, round stones (Grinnell, 1923, I: 198).

Note that here, as in Plate 106, in which it is probable that the same two men are riding together, the horse is ridden without reins, guided by knee pressure alone, and by the lead line attached to the halter latch. The two are riding together only for the parade, of course. Before starting away, Arrow will switch to his own horse.

There may be some significance specific to the Elk Society in the red cloth breastbands worn by four of the horses in this war party. Another is shown on Arrow's horse in Plate 2. Although one, similar band appears in the Dog Soldier parade in Plate 65, compare the 1898 photo of an Elk Society parade shown in Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 5, in which most of the horses are draped with similar necklaces of sleigh bells.