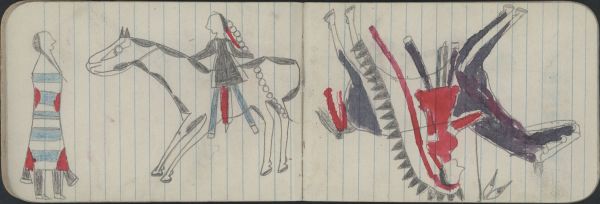

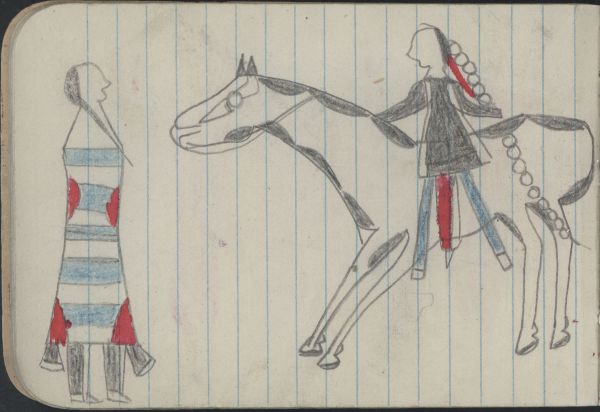

COURTING: Man on Gray Pinto Courts Woman in 2nd Phase Chief''s Blanket; WAR, WARRIOR: Man on Black Horse Carries a Lance

Ethnographic Notes

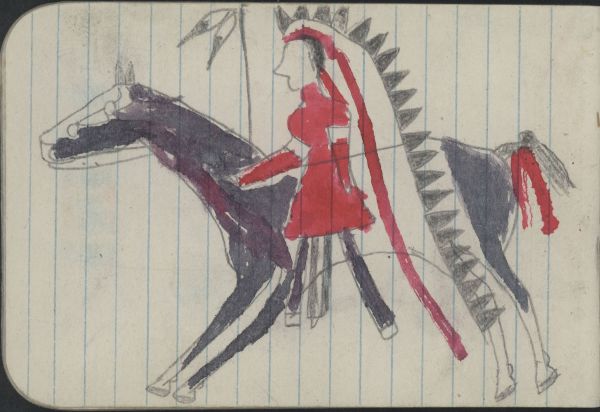

14 COURTSHIP, MAN. A man on a gray-and-white pinto horse. He wears a German or nickel-silver hairplate ornament and red-cloth wrapped braids. His outstretched arms show details of his gray cloth shirt with undyed selvedges running lengthwise from each shoulder to create stripes, and red leggings with a white stripe (undyed selvedge of the Stroud trade cloth). His breechclout is blue with white edges. The horse wears a silver or German silver headstall (see plate 8). The woman, on foot facing the horseman, wears a second-phase Navajo chief's blanket. Her leggings are gray with a vertical white stripe where undyed selvedges were sewn together to create the design. Her dress panels showing beneath the blanket are also gray with white edges. Her leggings and dress tabs match the man's shirt. She wears braids, and one is visible resting on her shoulder. The formal dress and pose suggest courtship (see Plate 8 for further discussion). See plate 1 for further discussion of courtship conventions. The man is in the active position in the drawing; Candace Greene describes the syntax of Cheyenne ledger art as moving, most often, from the dominant right-hand side to the left-hand side, described in her article "Structure and Meaning in Cheyenne Ledger Art" (Plains Indian Drawings 1865-1935, ed. Janet Catherine Berlo, New York: Abrams, 1996: 34-9). In her dissertation, she explains the typical bilateral composition of "the majority of Cheyenne pictures" (1985: 67). The two elements contrast: Cheyenne/ enemy; victor/vanquished; hunter/prey; man/woman (Greene 1985: 67-73). Another characteristic of this highly connotative sign system is simultaneity: "Every figure fills a number of categories simultaneously (male, Cheyenne, warrior, shield bearer, etc.), and our attention is brought to bear upon a particular one only by contrast with the other figure in the picture" (Greene, 1985: 67). This principle is evident in all the drawings, especially those with suitor/hunter/warrior figures to the right. Media: Pencil outlines, details and fill; blue crayon; red watercolor 15 reversed. A warrior sits in formal dress astride his black horse. He wears a single-trail headdress of black-tipped immature golden eagle feathers, attached to red trade cloth. He wears a red cloth shirt with nickel-silver armbands above each elbow. The shirt tails are not tucked in, as was the Cheyenne custom (Benson L. Lanford in Pamplin Ledger, 1999: 159). His leggings are made of dark trade cloth with undyed selvedge ends sewn together lengthwise along the seam, which creates a vertical stripe (Lanford, 2003: 201). His long breechclout is matching dark trade cloth with undyed selvedges at the ends. He carries a coup stick or lance with two eagle feathers tied to the top. The horse has a nickel-silver headstall and either a horse mask or natural markings on its head. The black horse's tail is tied with red cloth in preparation for war; it also has a white stripe painted up its front leg, similar to the man's legging stripe. Red paint appears on its chest. No features appear on the man's face, nor is there a name glyph. However, the details of dress are significant regarding identity and military accomplishment. Craig Bates describes how "the precise patterns and details of clothing would furnish a man's comrades with information that would allow them to identify the warrior who was being depicted" (2003: 15).This is one of the numerous warrior portraits in the 1879 Dodge City ledgers, and even though it is not an overt combat scene, the war regalia suggests warfare. The Northern Cheyenne men who drew this and related 1879 Dodge City ledgers avoided combat scenes with settlers and U.S. military personnel as they awaited trial for raids in Kansas (Low and Powers, 2012: 2-25). Joyce Szabo notes a similar shift in subject matter of Fort Marion ledger artists, also imprisoned (1875-1878): "Finally individual portraits and self-portraits appear throughout the known body of works created by the Plains warrior-artists in Florida" (Art from Fort Marion: The Silberman Collection, 2007: ix; 41). The largest number of Fort Marion artists, fifteen, were Cheyennes (Szabo, 2007: 177). Like the Northern Cheyenne artists of 1879 Dodge City, combat scenes were discreetly dropped from the repertoire by the imprisoned men. Szabo discusses this further as she quotes Captain Pratt�s papers: �Though fond of painting wild hunts, and war dances, and grand battles, they [Fort Marion prisoners] are not fond of recounting their own savage deeds, and confided to Captain Pratt that they do not like to be asked by visitors if they have scalped and killed people� (Box 43, folder 820, Pratt Papers, quoted in Szabo 2007: 178). The related Dodge City ledgers have few combat scenes, and none involves U.S. military men or settlers. Nonetheless, like courtship dress suggests courtship even if a man is alone, the warfare dress of individual men and their horses also suggests warfare. The crudeness of this drawing, especially the horse, resembles the style of the Clayton ledger, attributed to Wild Hog. This man, with almost identical headdress or a trailing German silver hairplate, appears repeatedly in this ledger, seventeen times, and most likely this is the same man or a close comrade (Plates 9, 10, 13-17, 26-35).