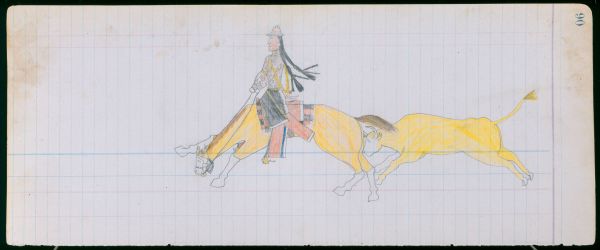

PLATE 90

Ethnographic Notes

This man is Arrow's comrade from the previous drawing, his face again painted red, and riding the same Indian saddle with bowed pommel and cantle. The folded, Mexican weaving laid over the saddle is probably intended as the same one also, although here the blue yarn is omitted. This is not the same buckskin horse, however, for it lacks the Mexican hip-brand, and has white legs below the knees.

Arrow has chosen to depict his friend in an embarrassing predicament, undoubtedly to the huge amusement of all their Elk Society fellows. A domestic cow is shown goring the Cheyenne's horse in the rump. Anyone who has seen a rodeo will understand that the horse's head-down posture and stiffened forelegs are the prelude to a series of pronking leaps that in a few moments more will have the Cheyenne sitting on nothing, save the breeze. We may presume that when he crashed to the ground the angry cow did him no further injury, or there would have been little humor to inspire this drawing.

The Union Pacific Railway---shortly renamed the Kansas Pacific---reached Abilene, Kansas, in March of 1867. By September, Texas cattlemen had already trailed the first herds of longhorns north from the area of present Dallas-Fort Worth, straight through the heart of the Kiowa, Comanche and Cheyenne buffalo range, for shipment from Abilene to the Chicago stockyards. Every year thereafter saw increased incursions on Cheyenne territory, as the railroad built further west, meanwhile transporting thousands of eastern emigrants to settle along the Smoky Hill route, searching for small-hold cattle range in all directions.

By the time the Treaty of Medicine Lodge was signed in October, 1867, the railroad had been extended nearly out to Fort Hayes. When Black Kettle's Cheyennes were massacred at the Washita in November, 1868, the Kansas Pacific "head of track" had advanced nearly to the Colorado line. All this time the Dog Soldiers and other Cheyennes were intermittently attacking the track crews, like spitting into a forty-knot gale, and trying to make the juggernaut go away. All through the spring of 1869 the Dog Soldiers fought valiantly, and held the track advance to less than 50 miles; but in July of that year the Army caught them at Summit Springs, killed their leading chief Tall Bull and many others, and burned their village---eighty-four lodges. Fourteen months later, on the first of September, 1870, the first Kansas Pacific train rolled into Denver. It had been exactly fifty years since the Cheyennes had encountered the Stephen Long expedition making their survey along the Arkansas (dates and distances from the Union Pacific Railway map published in Reedstrom, 1977: 7).

In the estimation of railway executives: "The cowtowns of Abilene and Ellsworth contributed much to the financial life of the railroad. Thousands upon thousands of Texas longhorns were started to the eastern markets over the Kansas Pacific from these frontier towns" (Reedstrom, 1977:7). That far understates the reality: in 1871 alone, 600,000 Texas cattle were driven north on the Chisholm Trail, right through the heart of the Southern Cheyenne country.

Between 1867 and 1880, nine to ten million cattle were trailed north from Texas to the Kansas railheads in "the largest migration of domestic animals in human history" (Encyclopedia Americana, 1995 edition, Vol. 6: 609).

The Chisholm Trail was not a simple cow path. Every one of the animals that went over it had four hooves---40 million sharp-edged spades---which, in less than fifteen years, harrowed a swath of country miles wide, transforming a verdant, prairie world into a super highway of dust and desolation. The Dust Bowl of the 1930's had its inception in those monumental cattle drives of the 1870's. The lilting cowboy refrain we all learned as children:

"Come a tai yi Yippee yippee yay Yippee yay Come a kai yi Yippee, yippee yay"

was the death song of the Cheyenne heartland.

In this drawing, made about 1874, Arrow provided a contemporary Cheyenne view of the animal which altered their world forever. Long before, in the 18th century, the great Cheyenne prophet Sweet Medicine had sent this warning down the years:

"Listen to me carefully. Listen to me carefully. (He said this four times.) Our Great-grandfather...made us, but also he made others. There are all kinds of people on earth that you will meet someday...

"Perhaps they will not listen to what you say to them, but YOU will listen to what they say to you. They will be people who do not get tired, but who...will keep coming, coming.

"...after a while a different animal will come into the country. It will have a head like a buffalo, but it will have white horns and a long tail. These animals will smell differently from the buffalo, and at last you will come to eating them. When you skin them the flesh will jerk, and at last you will get this same disease" (Grinnell, 1908a: 319).

We cannot deduce the circumstances which led to this incident---where, or how Arrow's friend encountered this cow. As cattle outfits increasingly encroached south of the Arkansas in the 1870's, the Cheyennes were unable to avoid such animals---and longhorns, like buffalo, are dangerous, as the drawing proves. From the Cheyenne's dress, and the appearance of his horse, we can judge that this was an unexpected contretemps: the man is wearing his best courting clothes, so no aggression was anticipated; and the horse is prepared neither for war (its tail is not wrapped), nor the hunt (the bridle is too fancy). The humor in the situation lies precisely there---the poor guy had just gotten dressed up to visit his girlfriend, when this crazy Whiteman cow dumped him in the creek.

Many Cheyenne names were occasioned by ridiculous accidents like this one: Bad Face Bull, Blind Bull ("He was run over by a..."), Blown Away, Chief Going Up, Dirty Nose, Dives Backwards, Flying Man, Hard Ground, Kicking Horse, Limpy, Man Above, Man Walking High, One Horn (in the rump?), Tangle Hair. Not all of these famous examples are necessarily joking names, but they might well be; and the Cheyennes have many such.

Arrow's friend has crowned himself with a very stylish cap, and we shall see it often hereafter. Actually, it is a cheap, white, felt hat that has gotten wet, and been stretched out of shape so that it looks rather like an inside-out sailor's cap. The Cheyenne has spruced it up considerably, however, by cutting vertical slits all around the hat, then weaving a strip of red ribbon or cloth in and out, to produce a broken, red line where the hat band would be; and finally, he daubed spots of blue paint all over the felt. It will become one of Arrow's hallmarks for identifying this man---see Plates 100, 112, 134 & 136. In Plate 136 this man and his hat appear facing Arrow in Plate 137, so there can be no possibility that this figure is a self-portrait. Another Cheyenne wearing similar headgear is shown by Powell, 1981: 359.

The man's parted hair is wrapped on either side with a short length of otter fur, the ends twisted, and allowed to hang down. Compare this otter wrapping with Arrow's scalplock in Plates 1, 13, 144 & 156. Like the twisted otter strips on Arrow's straight lance, and the hair wrapping of the yellow-painted man in Plate 163, these are probably an indication of membership in the Elk Society. Note in Plate 112 that this man has added to his standard red face paint a black zigzag of lightning below the eye. This is repeated in the Elk Society parade in Plate 163, where he rides together with Arrow on the same horse. Both men, therefore, are Elks.

His silk shirt has a spectacular pattern of white birds against a red background. Note how similar these are to the birds painted on the shield in Plate 17. The cloth may have been chosen by this man for particular, symbolic associations---the bald eagle, for example, with its white head and tail. Moore (1986: 185) says: "The bald eagle, Voaxa, is not as respected as other eagles, because it eats fish and carrion, and because it is the emblem appearing on United States money." This is surely a revisionist opinion, however, for bald eagles appear prominently on 19th-century Cheyenne war shields (see Powell, 1981: 371; Nagy, 1994b: Fig. 8, and 1997b: Fig. 3), as do also their feathers.

Over his shirt the Cheyenne wears brass armbands; and diagonally across his chest hangs a multiple-strand bandolier of brass beads, to which is tied a red packet of calico cloth containing a compound of fragrant herbs, similar to that worn by Arrow in Plate 88. His dentalium-shell choker has yellow-painted spacers. The long, red wool breechcloth and fully-beaded moccasins appear to be the same ones he wore in the previous drawing. There is a new pair of red trade cloth leggings, however, with blue silk ribbon embroidered along the white selvedge. He may have borrowed Arrow's dark blue courting blanket with yellow, silk-ribbon trim, now wrapped around his waist.

A significant and colorful detail is the depiction here, under the silver-mounted bridle, of a headstall made of plaited horsehair:

"The Southern [Plains] Indians have learned from the Mexicans the art of plaiting horsehair, and much of their work is very artistic and beautiful, besides being wonderfully serviceable. A small smooth stick of one-fourth of an inch in diameter is the mould over which the hair is plaited. When finished, the stick is withdrawn. The hair used is previously dyed of different colors, and it is so woven as to present pretty patterns. This hair, not being very strong, is used for the headstall; the reins, which require strength, are plaited solid, but in the same pattern, showing both skill, taste and fitness" (Dodge, 1882: 251).