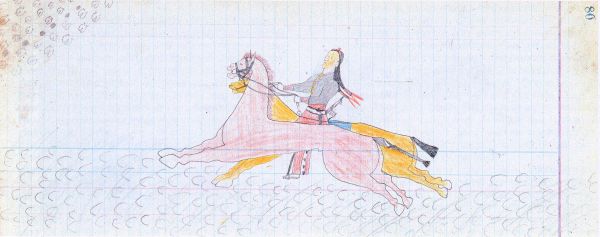

PLATE 80

Ethnographic Notes

Although not originally sequential pages, these two drawings, PLATE 80 and PLATE 86, belong together, for they nicely illustrate the approach of hunters to a buffalo herd, as well as the actual chase. Also, Arrow shows himself dressed nearly the same, and with the same horse in both drawings, so we may judge that both depict the same hunt.

Tribal hunts were closely regulated by one of the warrior societies, appointed by the camp chiefs differently for each occasion. In order that all hunters might have an equal opportunity to feed their families, it was important that no over-eager individuals be allowed to alarm and stampede a nearby herd, else the rest of the group might starve. Whenever scouts located a suitable herd, military law was quickly invoked. The chosen military society sent out its members to patrol the environs of the camp, and prevent anyone from starting earlier than the others. Everyone then knew who was in charge. Any orders given by the chosen society would be instantly followed. Any recalcitrant dissenters would be summarily whipped or otherwise punished, short of death. Their horses might be shot, or their lodges and property destroyed; for the welfare of all depended upon the good order and wise planning of the hunt leaders.

All Cheyennes understood this, and rarely was there any serious problem. Generally, it was excited teenage boys who fell afoul of the camp police, as Wooden Leg recalled:

"...[On] a buffalo hunt one time when I was about sixteen years old...I was riding with three other youths about my age...We skirted around the band of hunters and got forward...Four Crazy Dog warriors were right after us. They were riding fast. The other boys got away, but my pony played out on me. I had to stop and dismount. I was frightened to distraction...when four determined-looking...policemen dashed up to me.

" 'Do not whip me,' I begged. 'Kill my horse. You may have all of my clothing. Here---take my gun and break it into pieces.'

"But after a talk among themselves they decided not to do any of these penal acts. They scolded me and said I was a foolish little boy. That was the last time I ever flagrantly violated any of the laws of travel or the hunt" (Marquis, 1931: 64-66).

When a buffalo scout, such as Arrow depicts in Plate 67, returned to camp with news of a herd, the herald announced this discovery while riding slowly through the village:

"All Cheyennes, open your ears and listen. Many buffalo have been discovered by our scouts. Sharpen your knives and your arrow points. See that your guns are in good order. Have your riding horses and your pack horses ready. Tomorrow morning we go. The Elk warriors will lead and conduct the hunt" (Marquis, 1931: 63).

In one of his earliest publications, long out-of-print and generally ignored by scholars, George Bird Grinnell gave perhaps the finest description of a Plains Indian buffalo hunt:

"So the people made ready for the killing on the morrow. All the running horses were brought in and tied up, and the women had their pack horses close by the camp, where they could catch them in a little while. Every man had looked over his arms to see that his bowstring was right, that all of his arrows were straight and strong, and the points well sharpened. Some young boys who were now to make their first hunt were excited, and each was wondering what would happen to him, and whether he would kill a buffalo, and was hoping that he might act so that his father and his relations would praise him and say that he had done well.

"Many of the men prayed almost all night, asking that they might have good luck; that their horses might be sure-footed and not fall with them, and might be swift to overtake the fastest of the cows; that they themselves might have good sight to aim the arrow, and that their arms might be strong to draw the bow, so that they would kill much meat. They smoked and burned sweetgrass and sweet pine to purify themselves. Other men, having told their wives to call them before the first light appeared in the east, slept all through the short night.

"So now, the day of the buffalo killing had come. This morning everyone arose very early, and when the time came all the men, except those too old to ride...rode up on the prairie before the day broke. The eastern sky was beginning to grow light, and the stars dim; the air was cool with the chill that comes before the dawn, and there was no sound except the dull murmur of many hoof beats upon the prairie as man after man rode up and joined the others, until almost all were there and they started away...

"At first the hunters ride scattered out over the prairie without much appearance of order, some of them lagging behind, but most of them well up to the front. Yet none pass a line of men, the soldiers of the camp, who have the charge of the hunt; for today these soldiers are the chiefs, and everything must be done as they direct...So the soldiers ride ahead of the hunters slowly, keeping back those who wish to hurry ahead, giving time for those who are late or who have slow horses to catch up, so that when the word shall be given to charge the buffalo, each one may have an equal chance to do his best.

"They ride on slowly, in a loose body, some hundreds in all, going no faster than the soldiers who ride before them. Now and then, men who have been late in leaving the camp come rapidly up from behind, and then settle down into the slow gallop of the leaders. By this time the sun is rising, and flooding the prairie with yellow light; the grass, already turning brown, is spangled with dew and glistens in the sunlight. The sweet wild whistle of the meadowlark rings out from the knolls, and all about the skylark and the white-winged blackbird are hanging in the air, giving forth their richest notes...

"The men do all they can to spare the horses that they wish to use for the running. Some trot along on foot beside their animals, resting an arm on the withers; others ride a common horse, and lead the runner until the moment comes for the charge; or two men may ride a common horse, one guiding it and the other leading the two runners. Mile after mile is passed over at a slow gallop until the spot where the buffalo were feeding is reached. Here the company is halted, and two or three of the soldiers creep forward to the crest of the hill and peer over...

"A sign from the chief of the soldiers warns everyone that the time for the charge is at hand. The common horses are turned loose and the runners mounted; bows are strung, and arrows loosened in their quivers. Men and horses give signs of eagerness. The horses, with pricked ears look toward the hilltop, while the movements of the men are quick. At another sign, all mount and ride after the soldiers, who are passing over the crest of the hill. All press to the front as far as they can, and now, instead of being in a loose body, the men ride side by side, with extended front. As they descend the slope toward the buffalo the pace grows faster, until the swift gallop has become almost a run, but as yet no man presses ahead of his fellows, for the soldiers hold their places...

"In the flat before them, scattered over the level land like cattle in a pasture, the buffalo still feed, undisturbed...In a moment, however, all this is changed: the buffalo begin to raise their heads and look, and then...the herd, panic-stricken, turns away in a headlong flight. As they start, the leader of the soldiers gives the signal so long looked for. All restraint is removed. The line breaks, all semblence of order is lost, and a wild race begins, a struggle to be first to reach the buffalo, and so to have choice of the fattest animals in the herd.

"Each rider urges his horse at his best speed. The fastest soon draw away from the main body and are close to the herd; the hindermost buffalo are passed without notice, and the men press forward to reach the cows and young animals which lead the band. The herd is split in twenty places, and soon all is confusion, and horses and buffalo race along side by side. Over the rough billowing backs of the buffalo the naked shoulders of the men show brown and glistening, and his long black hair flows our far behind each rider, rising and falling with his horse's stride. The lithe bodies swing and bend, and the arms move as the riders draw the arrows to the head and drive them to the feather into the flying beasts.

"It is hard to see how those who are riding in the thick of the herd can escape injury from the tossing horns of the buffalo, now mad with fear, but the ponies are watchful, nimble and sure-footed, and avoid the charges of the cows, leap the gullies, and dodge the badger holes...

"All along where they have passed, the yellow prairie is dotted here and there with brown carcasses, among which stand at intervals buffalo with lowered heads, whose life is ebbing away with the red current that pours from their wounds, but whose glaring eyes and erect stiffened tails show that they are ready to fight to the last breath..

"It is not long before most of the buffalo have been slain, and the men come riding back over the ground to care for the animals they have killed, each one picking out from the dead those which belong to him. These are known at once by the arrows which remain in them, for each man's shafts bear his private mark..." (Grinnell, 1908b: 73-78).

In Plate 80, Arrow shows himself hurrying to catch up with the other hunters, whose many tracks he is following. In a perspective shift at upper left, he shows the tracks of buffalo---calves as well as adults---intersecting the path the hunters have taken. Arrow rides the buckskin of Plates 76 & 79, conserving the strength of his favorite, bay buffalo-runner, already seen in action in Plate 72. Its tail has been braided, indicating the horse is intended for hard riding; and Arrow's small, protective feather is tied to the tail as well. Note that the bay is so eager for the chase, he is actually running ahead.

The buckskin has a low, Indian-made saddle, with curved bows, commonly used both for riding, and for packing butchered game (Grinnell, 1923, I: 206).

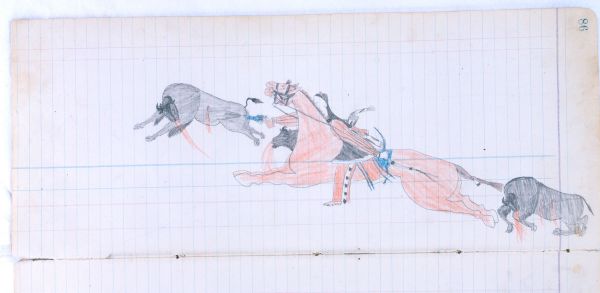

Arrow wears partly-beaded moccasins with a V-shaped design around the edge of the foot, and short fringe down the toe. See Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 26h, for an actual pair of Cheyenne moccasins of this type. His red wool leggings with beaded strips are the same we have seen in Plate 32; they will appear again in Plate 120. Arrow's hunting shirt is of red cotton or silk, with black stripes. In Plate 80 he wears over this shirt a U.S. Army enlisted man's fatigue blouse, with brass buttons. He may have captured this in an encounter like that shown in Plate 5, and used it thereafter as an overcoat. The breechcloth, seen only in Plate 86, is of red wool trade cloth accented with four strips of blue silk ribbon.

In Plate 80, Arrow has a red wool blanket belted around his waist. In Plate 86 this has become a dark blue (black) blanket. This might indicate that the drawings represent different occasions, since two, intervening sheets of the ledger are missing. However, it is equally likely that the dark blanket in Plate 86 was an artistic substitution to avoid showing an entirely-red figure riding a red horse. In Plate 86, Arrow has also acquired a braided-rawhide quirt.

Arrow's weapons include his Whitney Navy revolver---seen in its holster in Plate 80, and being fired in Plate 86; as well as a blue-painted bow, and arrows, carried in a bowcase and quiver made of black-and-white spotted domestic cowskin. Their spotted markings made cowskins quite a popular choice for bowcase-quivers. Many Cheyenne drawings show them. Wooden Leg, describing the year 1877, remembered: "My mother made a pouch for [my] bow and arrows. She made it of a calfskin she had tanned..." (Marquis, 1931: 314). Grinnell gives a photo of such a Cheyenne bowcase-quiver, with its bow and arrows (1923, II: opp. 144).

In Plate 80 Arrow's face is covered with his yellow Elk Society paint, and a short, black line beside his eye. This paint is not represented in Plate 86, but there Arrow's face is partly obscured. Note the tiny red feather attached to a red-painted thong, and tied to the top of Arrow's head. This is very likely a protective talisman, and must be related to the similar, black example worn by Arrow's relative in Plate 79.

Late though Arrow may be in Plate 80, he must have caught up with the band of fellow hunters before they reached the herd, for he is doing splendidly in Plate 86. If he had not had an even start, the animals would have been scattered and driven away, spoiling his chances. When the hunters stopped to scout the herd, Arrow quickly switched the blue riding pad from the buckskin to the bay, to use as his seat during the hunt. The saddle was left on the buckskin.

The action in Plate 86 has jumped ahead, to the end of the chase. The Cheyenne has already shot away all of his arrows, probably accounting for several downed animals. With the bow still gripped in his left hand, Arrow has drawn the revolver and is just shooting the third buffalo. Note that he again has selected cows for their more-tender meat, and thinner, more easily tanned hides. Compare Plate 72.

A final leitmotif of Plains buffalo hunting is worth noting: "The ravens and crows used to follow the hunting parties. They smell blood a long way. Whenever Indians killed buffalo, you could always see them coming in flocks to get something to eat" (Bent, 1904-1918: May 6, 1918).